I used to be very interested in names and naming culture. I used to ask people where their names came from or what pet names were common in their country. It’s not that I’m not interest in names anymore. It’s just that other interests have superseded that interest. I want to return to it, though for this post.

I love my English name. Brendan Farrell Ryan. Each word, two syllables, creating a nice weight. I like the story this name tells about my life and my family and my background.

I’m an October baby. The family story goes that around the time I was born, my brother and sister were watching this Dr. Seuss VHS tape, Halloween is Grinch Night. The short movie is some strange Who/Grinch crossover. A product of the 70s. A feverdream, really.

One of the main characters is named Euchariah Who. My brother and sister loved the name and insisted my parents name me Euchariah. My parents decided otherwise, but the name stuck as a nickname. I went by Eukie and Brendan until I started school. Some relatives still call me Eukie.

Brendan

I was named after an Irish Saint, Brendan the Navigator. My dad picked the name. Out of everyone in the family, he’s the one who feels most connected to our family’s ancestral Irish roots. My parents raised us Catholic, so it tracks they wanted to name me after a saint.

I’m not sure if I believe in names as prophecy or not, but I do sometimes return to that concept when I think about my own name. Brendan. The Navigator. On the day-to-day level, I have an excellent sense of direction. In the grander life-sense level, I wonder if there’s something prophetic about my name. I live outside my own country. I travel.

Or maybe that’s a bunch of bullshit.

I’m glad to be named after a saint and not after a dead family member. In the cultural spaces I inhabit these days, it’s taboo to be named after a dead relative.

Farrell

Farrell is my mother’s maiden name. I don’t think it was some feminist statement to give me this as a middle name. It’s not exactly a family tradition, as far as I know. My sister’s middle name is different. My brother and I share the same middle name. Regardless, I like the idea that in my name, I carry both my mother and my father.

Ryan

Ryan reads as very Irish. I used to find it annoying to have a first name as a last name. The number of times I’ve gotten called Ryan is…a lot…but it doesn’t bother me anymore. Sometimes, I do wish my parents had named me Ryan Ryan Ryan. It’s a name that begs to be noticed. I am a writer. I want my name to be noticed.

When I publish my writing anywhere, whether it be on this Substack or elsewhere, I put my full name. Brendan. Farrell. Ryan. This is very international.

If you Google “Brendan Ryan,” it’s mostly details about this baseball player. If you search “Brendan Ryan writer” you get results on a poet. That poet is not me.

Are you fucking kidding me? There’s a poet. And his name is Brendan Ryan. Same spelling as mine. We can’t let that happen. So I put in my middle name. Spell the whole thing out. In an effort to be different.

My handle on all my social media (@thebfryan) confuses people sometimes. “Best friend Ryan?” “Boyfriend Ryan?” It’s my name. The Brendan Farrell Ryan. I came up with it when I created my Instagram 10-years ago. I remember thinking that, whatever I picked was going to stick with me.

This isn’t the only name I use, though.

Call me…Jean-Claude?

I had forgotten about this until writing this piece, but in high school when taking French class, the teacher had us pick French names. I picked Jean-Claude, which felt very French to me at the time, and was also a way to pay homage to Christo and Jeanne-Claude, who I had recently learned. We made name tags in class. I drew yellow and blue umbrellas on mine.

I don’t think our French teacher even used our French names for us, though. I’m interested in this idea that, when you learn some foreign languages in the US, you get a new name. That’s going to frame a lot of the rest of this piece. I imagine now, if I were to go to France, introducing myself to people.

“My name is Brendan, but you can call me Jean-Claude.”

It feels like an act of insanity.

But I do have a Chinese name that I use. A name that I love. A name I feel I truly inhabit. It’s not some arbitrary name picked on the first day of class. It is a part of me.

阿舜

The first time I studied Mandarin was the summer between my junior and senior year of high school. I attended the StarTalk program at the University of Mississippi, a program I would later work for. It was one-month of intensive Mandarin classes paired with cultural activities. That program was the start of an important shift in my life. It’s what got me interested in Mandarin, got me comfortable with the idea of maybe attending the University of Mississippi for college.

The first day of class, the teacher asked us some basic information about ourselves. Our likes. Our dislikes. The next day, we were given Chinese names. We were never asked if we wanted these names or not. These are the names we would then carry with us the rest of the program. I don’t remember mine. I never felt a connection to it.

There’s lots of different ways a learner of Chinese can pick a Chinese name. Some names are picked based on them sounding like your English name. Others are based on the meaning of your English name. You can convert English names into Chinese names phonetically. My full name would be 布倫登·法瑞爾·瑞恩. This name is a mouthful to pronounce. Celebrity names are often written out like this.

A slight sidenote, but these’s this meme from Taiwan where this TV host was reading out news about Leonardo Dicaprio. She gets his first name right, but when she’s saying his last name, instead of saying Dicaprio, she says Pikachu. I have watched this video so many times. I love news bloopers and this one is particularly good.

When I went on my gap year in Taiwan, the program asked if we had Chinese names. I lied and said no, I had never been given one. That meant someone in the program would need to give me one, be it a teacher or my host family.

My host family ended up being the ones to pick my name, to gift me a name, one that has stayed with me to today, and I consider one of the most precious gifts anyone has ever given me.

My name in Chinese is 王新舜, which in Mandarin is pronounced Wang2 Xin1shun4. I’m particular about the use of the word “Chinese,” because it’s kind of meaningless in describing a language. “I speak Chinese.” Do you mean Mandarin, Cantonese, Shanghainese, Taiwanese, Sichuanese……..? Here, when I say Chinese, I’m referring to Chinese characters, which are used to write the name. The name itself can be pronounced in a variety of different languages, including all the ones I listed above. Those three characters can also be pronounced in Vietnamese, which I’ll get to later.

When I tell people my name, people often comment that it’s a very bold name. 舜, the last character in the name, is the name of a legendary emperor of China. 新 means new. There’s a sense in the name of being a new version of a great mythical figure. It is a strong name.

Inevitably, I get asked who gave me this name. The name is different than the typical names white American learners of Chinese have. It doesn’t sound like my name at all. It’s not clunky, either, like many of the names people pick for themselves. It’s also a very good name, well-selected and references a semi-historical figure that everyone knows.

It’s very easy to explain this name to Mandarin speakers. It goes something like this—

“I lived with a host family in Taiwan. They had a son named 新堯….”

The listener lets out a of sound showing they understand, that my name now makes perfect sense to them. I love the ease of this explanation in Mandarin.

The English explanation is a bit longer, because it requires explaining all these connections that a Mandarin speaker is making instantaneously on hearing the name, connections based on an understood naming tradition, on cultural knowledge, on the significance behind the name.

舜, who I’m named after, is a legendary emperor. Before him, there was a different legendary emperor named 堯. Chinese names typically have three characters (though they can have two or rarely four). Some families will name children after something similar to show they’re related. In my case, my host family gave me this name, which is identical to my host brother’s name except the last character, to show we are related, part of the same people. It is a symbolic gesture of acceptance. It’s so incredibly generous and reflects their openness to accepting a stranger into their home.

They actually kept up this naming practice. I was the first American student they hosted. After me, they hosted four other students, and those students all were given names in the order of these legendary Chinese emperors.

I like this name for so many reasons. It gives me a lot of credit immediately. It signals to the listener, this guy doesn’t just speak Mandarin, he speaks Mandarin. I’m going to write about this later, but as a white speaker of Mandarin, there is often this period when interacting with new people where I have to show that I have a certain, basic cultural understanding, and whoever I’m interacting with can relax and speak normally, make specific cultural references, use casual language. My name helps smooth this over very quickly.

My Mandarin-speaking friends feel very comfortable using it with me. I get all sorts of nicknames from it. Some of my friends call me 大舜, big Shun. Others call me 阿舜 A-shun, which is perhaps less a nickname, and a tendency for people from Taiwan and southern China to add 阿 before the final character of someone’s name. Not only was I given a name, I was given a name that is easily nicknameable.

My Chinese surname, 王, means king. My English last name, Ryan, means little king. This is a total coincidence. It’s perfect.

There’s sometimes an issue where someone’s name sounds great in Mandarin, but when you pronounce it in a different Sinitic language, it sounds funny. Or the Mandarin pronunciation sounds like something funny in another language. The first example that comes to mind is Subway, which is called 赛百味 in China. 赛 sounds like the Taiwanese Hokkien word for shit, and the full name sounds like “100-flavors of shit.” Like Leonardo Pickachu, I find this endlessly funny. On a quick poke around on the Taiwan Subway website, I also noticed that they seem to just use the English word “Subway.” This is all to say, at least in Hokkien and Cantonese, my name sounds normal.

There’s one slightly annoying thing about my Chinese name. There’s kind of this art to introducing how to write your name in Chinese. There are lots of homophones in Chinese. When I say my name, Wang2 Xin1shun4, people might not actually imagine the right characters for the name. They might think 心 xin1 is heart. Or they might think 順 shun4 is from 順利 shun4li4, which is a pretty common response I get. People almost never automatically imagine the actual character in my name.

It’s easy enough to explain. 新 xin1 as in 新年 xin1nian2, new as in new year. 舜 Shun4 as in 堯舜禹, you know, the Shun4 who’s the legendary emperor.

I’ve spent all this time really expressing thanks and joy and love for my Chinese name, but I also wonder about giving names as a practice. Names matter. Part of why I feel so comfortable in Taiwan and China is because of my name. I also got lucky being gifted such an excellent name.

Names are treated as so commonplace, but I think the stakes around them are really high. It’s something people will use to label you. It’s easily a space for people to make jokes about you. I was an effeminate little boy named Brendan. I know what it feels like to be called Brenda on the playground.

There’s so much weight around names, and I don’t think that that weight has ever been examined in any Mandarin course I ever took. Names seem to be given out with the students not having much say in what’s happening, and nobody is questioning, “Do you want a Chinese name?” Nobody ever said, do you want to get your fortune told first, see what type of names suits you, a practice common enough in China and Taiwan.

While writing this, I started to imagine, what if in my university’s Chinese department I had said, “I don’t want a Chinese name. I want people to call me my English name.” As far as I know, nobody has ever done this. I would have never done this, because my approach to cultures other than my own is to try to fit in (more on that later), so I wouldn’t have pushed back against norms in that way. But what if?

I’m not saying students shouldn’t have Chinese names. There’s definitely an expectation in China that you’ll have one as well. I just wonder if they’re being given too early, before students can grasp what a name means. Of course, you can always change your name.

I used to really care. When friends called me my English name, I felt uncomfortable. Did they not accept me? Was my Mandarin not good enough? Now I don’t really care. Call me by whatever, as long as it’s one of my names.

But you don’t have a Vietnamese name?

I don’t have a Vietnamese name. I don’t want one, either. Not now, at least. I also don’t feel the need to have one.

In China, I felt this expectation to adjust myself to Chinese culture. In Vietnam, I feel a sort of opposite pull, that many of the Vietnamese people I interact with feel they should adjust to me, accommodate to my needs, make me comfortable. Whether their actions actually make me comfortable or not is a different discussion, but I see the attempt.

This is evidenced in so many aspects of my life. Walking into most restaurants, staff will either address me in English immediately or frantically call back for the one staff member in the back who speaks the best English. My teachers frequently over-explain basic aspects of Vietnamese culture with the foreign student audience in mind. Sometimes on public buses here, the drivers and bus workers are very concerned about where I’m getting off, making sure I know how the bus works.

There’s probably a whole essay in how these interactions make me feel (which frankly is generally annoyed, I don’t like attention in public spaces), but I do want to acknowledge the intention behind the action is to help me, to accommodate to me. I try my best to appreciate it, to find gratitude.

In comparison to how I feel in relation to Taiwan and China, I do feel a distance between myself and Vietnam. I’ve been thinking about that a lot. I will write more on it later, perhaps privately in my journal, or maybe on here. I’m not sure yet.

I think part of it is because of how I interact with Vietnam, as a place of study. It feels so sterile sometimes the way we talk about Vietnam in class. We so rarely address contemporary issues in Vietnam. Outside of class, I don’t want to interact much at all. With anything or anyone. I spent a lot of my time not in class alone.

Where this intersects with naming culture, is I don’t feel this external push to conform to Vietnamese society, which is so vastly different than how I experienced China. My own feelings around assimilation attempts have also changed pretty radically (which also warrants its own essay for deeper examination. So much to write about.).

In Taiwan, I was living with a Taiwanese family, speaking Mandarin at home with them, eating the amazing food they cooked for me, and hanging out with them at night. I wanted to blend in as much as possible, even if that meant sacrificing my own personal comfort. The name was part of this fitting in. I felt fairly incorporated into that family. In China, I wanted to be accepted so much, to be seen as someone who got how China worked and spoke Mandarin well, who was in on the cultural nuances. It’s impossible, of course, as a white person in China or Taiwan to assimilate, but in some ways I think that’s what made me try so much harder to fit in, to try to stand out as little as possible, to gain acceptance.

Where I’m at now is that I want to be me. I’m less willing to make large adjustments in order to fit in. I maintain the belief that I should be respectful within this cultural context, but I’m not seeking acceptance or validation from society as a whole. Most of the time, I care very little how strangers view me. At this stage, I don’t see the need to get a new name while here in Vietnam. If my not having a Vietnamese name was seen as some affront to Vietnamese culture, I would get one immediately. That’s not the case, though. Nobody seems to care strongly either way.

Script is a factor in names as well. It’s so easy here to just use my English name since English and Vietnamese both use the Latin alphabet. When I took Korean for one semester in university, our teacher had us write our names in Hangul. I imagine if you study Russian you have a way of writing your name in Cyrillic. In Vietnamese, it feels there’s no scriptal push for me to modify my name.

Of course, names aren’t just written. My name is pronounced a variety of ways here, depending on someone’s English knowledge. My teacher generally Vietnamize it. My friends don’t. I don’t really care either way, honestly. Sometimes I go by “Ryan” because it’s easier.

Since Chinese names can be so easily be written in Vietnamese, I initially had a period of time when I thought about just using my Chinese name pronounced in Vietnamese, Vương Tân Thuấn. But that didn’t feel right either, because it just sounds like a Chinese name. Part of coming to Vietnam was an intential pivot away from China in order to learn more about the world. Using my Chinese name feels exactly the opposite of that.

I have one friend who calls me Thuấn, and it’s very sweet and feels special, intimate but not in a romantic way. It’s more like a pet name. It’s not a name I want to use with everyone. It doesn’t fit me in Vietnamese because it doesn’t feel like a Vietnamese name.

I do wonder if some point in the future if I’ll feel differently about this, if I’ll want one. Or if I’ll be gifted one, like I was my Chinese name. I’m not closed off to the idea of having a Vietnamese name or a nickname everyone uses. If that happens, I want a name that feels correct.

On a language note, one of my favorite features of Vietnamese is that you can speak in the third person when talking, and people can refer to you by your name instead of using a pronoun. A conversation might go —

Friend to me: Where did Brendan go this afternoon?

Me: Brendan went to the store.

It took me a while to get used to referring to myself by name in conversation. The third person is depicted in so much media as the language of the strange. It took a while for it to feel normal, but I like it now, as this thing that strips away identifiers like age, status, or gender. A name is just a name.

Adults

In Taiwan, I got asked a lot, “What do you call your parents?” “Mom and dad.” “Not their first name?” “Oh god, never.”

I met people who got this idea from American cinema that Americans call their parents by their first names. Maybe in some households people do. I only ever refer to my parents by their first names when I’m being ironic or making a joke.

I do have a changing relationship with how I talk about my aunts and uncles. As a kid, I would always refer to them as “Aunt + First name” but now I sometimes just call them by their first name. It’s a gesture into adulthood, I think. I do this when talking about my parents’ friends. Where I’m from, we call adults by “Mr./Ms + first name.” So if my parents had a friend named Georgia, I would refer to her as “Ms. Georgia.” I drop the Mr.Ms. these days as well.

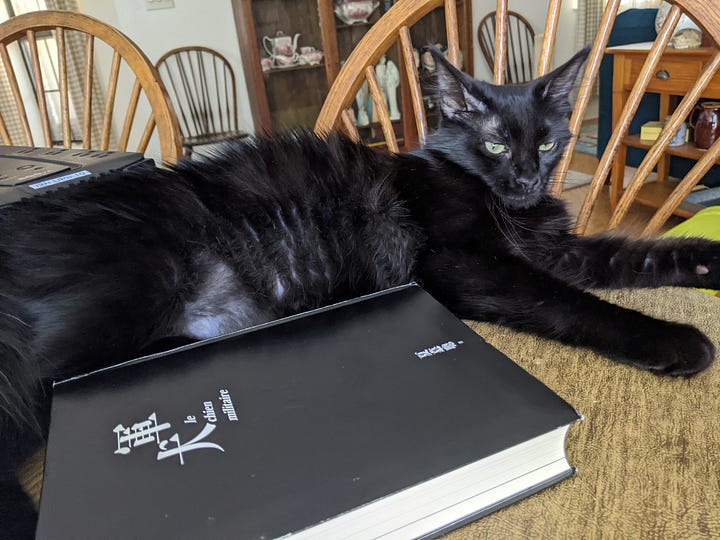

Pets

I’m also interested in what people call their pets. We went through a period where all ours cats were named after foods. Pancake. Waffles. Creampuff. Then we did human names for a while. Now my parents have two cats, one who is orange and appropriately named Flame. The other is named Fiona, because Fiona comes from a Gaelic word meaning “white” and she’s a black cat. Makes sense, right?

Fiction

I’m a little too precious with names when I write. I struggle so much when writing short fiction to come up with character names. Since I believe so much in the power of names, I don’t just want to give my characters arbitrary names. At the same time, I also don’t want the names to be too on the nose or cliche. Finding that balance can take me ages, and I often can’t start properly writing a story until I’ve named all the characters.

These days, I rely a lot on obituary pages. If I’m writing about a character from New Orleans, for example, I’ll browse obituaries from New Orleans, Frankensteining first and last names together until the character feels right. I read the obituaries too, and sometimes the lives of these people spills into the work. Sometimes it doesn’t.

If I know the date a character was born (I always at least have a rough idea), I check popular baby names around that time. I rely heavily on feeling, browsing name pages until one stands out to me, calls to me.

I wish I could just pick stand-ins for characters, call them A or B or C or whatever until the story is finished. I could write faster if I could bring myself to do that.

The end

I’m grateful these days to be in Vietnam, to be living in a place with spaces where I can use the names I want to use when I want to use them. Names matter.

Love this! And I'm jealous/fascinated by your Mandarin name. That is such a special honour and keepsake.

Your post comes at a time when a colleague and I have been talking a lot about the Vietnamese and English names of our students and all the related nuances. I think the presence of English classroom names is so outdated, but yet I understand its purpose. It raises the question we've both considered of how comfortable a person is with the mispronunciation of their name. It's hardly a topic for young children when they begin English lessons, but I wish it could be.

Also! I have never experienced any of the shepherding you mention here, such as finding an English speaker in a business or drawing attention on a bus. Beyond the service workers who will default to English (and now I just view it as their opportunity to practice), I feel almost ignored or a nuisance to some. One thing I feel a lot but don't know how to articulate (or prove...) is how different foreign men are treated here than foreign women. In many different situations. There's so much to unpack, so I tend to just say what I've said and then feel too ignorant to continue. Ha.